I posted a book list earlier this month, and a surprisingly large number of people have shown interest. So I thought maybe I should explain myself, as best I can.

I posted a book list earlier this month, and a surprisingly large number of people have shown interest. So I thought maybe I should explain myself, as best I can.

Most allies of Indigenous peoples seem to be non-Indigenous settlers in Indigenous lands. I am an indigenous British woman – the small ‘i’ denotes that I am a native of a colonising, not a colonised, country. I do not see Indigenous peoples on the streets of my country; I rarely read about them in my national newspapers, and when I do, they are in the international section that reports news from other countries.

So why am I an Indigenous ally?

Good question.

I wasn’t taught about colonisation at school. Our history lessons were all about British and European monarchs, mostly kings, and wars and conquests. People of colour didn’t feature (I wonder, now, how my school-friends of colour felt about our history lessons) and women played bit-parts.

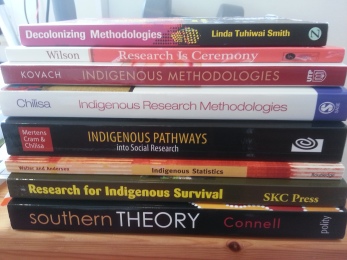

I didn’t like history at school, I think mainly because I didn’t identify with the people it featured (not being royal, or a man). When I was in my 20s, more interesting history books began to be published, including Peter Fryer’s groundbreaking works Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain and Black People in the British Empire (and The Women’s History of the World by Rosalind Miles, but that’s a different blog post). These books taught me some things about the roles people of colour had played in the history of my people, and about how my people had oppressed and exploited others. Then ten years later, when I was doing my masters’ degree in social research methods, the first edition of Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s seminal work Decolonising Methodologies was published. That book taught me about the role of research in colonialism.

It horrifies me that a majority of my fellow Brits think we should be proud of our Imperial legacy, and that over three times as many people think colonised countries are better off as a result than think they are worse off. It seems to me, from all I have read, and heard, and seen online, that the opposite is true. Colonisation is also, usually, spoken of as something that is past. I don’t agree with that either. Professor Bagele Chilisa of Botswana expresses it beautifully:

Colonization can be described as an attempt by the Western world to order the whole world according to Western standards of culture, politics, economic structures, and policies. (2012:81).

This is still happening. For example, several UK honours, given to British people by our Queen for exceptional achievements or service, still reference the British Empire. More broadly, Western peoples are still getting richer from colonisation, e.g. through buying cheap clothes made, or cheap food grown, by people of colour who work in appalling conditions for very little money. There must be many other examples of the Western world dictating how other parts of the world can act. I haven’t been able to find any research quantifying the current benefits accruing to colonisers from colonisation – we need a political economist with skills equivalent to Peter Fryer’s – but I am certain they exist.

This is so wrong and so unjust that it needs bigger words than ‘wrong’ and ‘unjust’. It is evil and I want no part of it, but I am a white person from a colonising country so I have a part in it whether I want one or not. The question that remains for me, then, is how to play that part.

I’m still figuring that out. Some things I know to do, such as shop and bank as ethically as possible, and talk to other white people about our role in colonialism and oppression. I support Indigenous activism where I can. I am reading, citing, and promoting Indigenous literature in my field. I think, too, that I may be able to help with my own writing – particularly my next book, and the second edition of my last book which will follow in due course.

There are probably other things I could do and should do. If you have thoughts or ideas, please pass them on in the comments. There are also things I would like to do. Last year I was able to attend one 90-minute seminar presented by Indigenous researchers, and the year before I was able to help an Indigenous researcher plan a couple of research projects they wanted to do (I learned at least as much as they did). Apart from that, all I have learned has come from books. I would love to spend some time with one or more Indigenous communities, to learn some of the things that can’t be learned from books, such as: how to be a better ally.

Clare Land has written a very good book called Decolonizing Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles (2015). It is really useful, but as Land is an ‘Anglo-identified non-Aboriginal person living and working in south-east Australia’, it is inevitably focused on Australia. I wonder whether I could write something on how to be an ally for coloniser people who are not settlers. It would be different from Clare Land’s book, though I don’t know in what ways. I hope, over time, I may be able to find out.

Feedback can feel like a very mixed blessing at times. Positive feedback is a delight to receive, while even the most constructive criticism can come as a crushing blow. Writers are particularly susceptible to this, especially novice writers who haven’t yet learned to separate critique of their writing from critique of themselves. I often meet doctoral students who are very reluctant to show their work to their supervisors, fearing criticism because they’re worried that it’s not very good. If it’s a first draft, of course it’s not very good, and a second draft will also contain problems that have to be fixed. Supervisors need to see this work so they can give feedback, which should include information about:

Feedback can feel like a very mixed blessing at times. Positive feedback is a delight to receive, while even the most constructive criticism can come as a crushing blow. Writers are particularly susceptible to this, especially novice writers who haven’t yet learned to separate critique of their writing from critique of themselves. I often meet doctoral students who are very reluctant to show their work to their supervisors, fearing criticism because they’re worried that it’s not very good. If it’s a first draft, of course it’s not very good, and a second draft will also contain problems that have to be fixed. Supervisors need to see this work so they can give feedback, which should include information about: Last Thursday, Friday and Saturday I was privileged to facilitate the inaugural Creative Research Methods summer school run by

Last Thursday, Friday and Saturday I was privileged to facilitate the inaugural Creative Research Methods summer school run by  Last week I wrote about

Last week I wrote about