A couple of years ago I compiled a reading list on Indigenous research methods which proved surprisingly popular. So here’s a follow-up, focusing on decolonising methods and methodologies. Again, it is what I have on my shelves; books I have read, used, and found worthwhile. I am not presenting this as any kind of an exhaustive or authoritative list. It doesn’t include some books I would love to have, because they are too expensive. As an independent researcher with no academic library nearby, I do buy books regularly, but my budget is limited so I have a ceiling of £30 or equivalent per book. Also I prefer not to buy secondhand as I know how much hard work goes into writing a book and how little authors make from their books; I don’t want to make that ‘little’ even smaller. On the plus side, I now write for three academic publishers which means I get author discounts. So, from one of them, I have ordered the second edition of Bagele Chilisa’s Indigenous Research Methodologies, as well as a book recommended by a commenter on my previous reading list post, Alternative Discourses in Asian Social Science by Syed Farid Alatas. Also, I just broke my own rule! Ever since it came out I have wanted a copy of Indigenous Research: Theories, Practices and Relationships, edited by Deborah McGregor, Jean-Paul Restoule and Rochelle Johnston. But it’s over £60 everywhere, so I scrolled on by. However, I just had another look and saw that it’s 950 pages long – which is at least three books, right? So now that’s on order too.

A couple of years ago I compiled a reading list on Indigenous research methods which proved surprisingly popular. So here’s a follow-up, focusing on decolonising methods and methodologies. Again, it is what I have on my shelves; books I have read, used, and found worthwhile. I am not presenting this as any kind of an exhaustive or authoritative list. It doesn’t include some books I would love to have, because they are too expensive. As an independent researcher with no academic library nearby, I do buy books regularly, but my budget is limited so I have a ceiling of £30 or equivalent per book. Also I prefer not to buy secondhand as I know how much hard work goes into writing a book and how little authors make from their books; I don’t want to make that ‘little’ even smaller. On the plus side, I now write for three academic publishers which means I get author discounts. So, from one of them, I have ordered the second edition of Bagele Chilisa’s Indigenous Research Methodologies, as well as a book recommended by a commenter on my previous reading list post, Alternative Discourses in Asian Social Science by Syed Farid Alatas. Also, I just broke my own rule! Ever since it came out I have wanted a copy of Indigenous Research: Theories, Practices and Relationships, edited by Deborah McGregor, Jean-Paul Restoule and Rochelle Johnston. But it’s over £60 everywhere, so I scrolled on by. However, I just had another look and saw that it’s 950 pages long – which is at least three books, right? So now that’s on order too.

All of which means there will be another update to this reading list in time to come. But now, back to this one. As I’m focusing on decolonising methods this time, I’m not only featuring Indigenous literature, but also subaltern literature. ‘Subaltern’ is used in post-colonial theory to mean individuals and groups who do not hold power. So, it could be said that Indigenous peoples are also subaltern, but subaltern peoples may not be Indigenous. Please note that this is only one option: these terms (like all those in this field) are contested, and self-definition always counts for more than externally applied categories. What this does illustrate is that decolonising methods is a project that implies scrutinising and decolonising a whole load of other things too, because methods don’t exist in isolation.

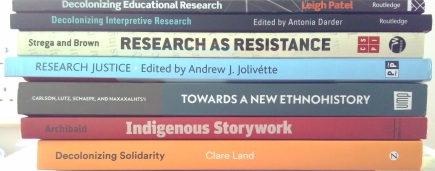

I’ll start with Decolonizing Educational Research: From Ownership to Answerability by Leigh Patel (2016). This is a beautifully written book which interrogates the ways in which Euro-Western educational systems support colonialism. Patel demonstrates that even apparently ethical concepts such as social justice can ‘become a vehicle for settler logics and heteropatriarchal racist capitalism’ (p 88). She shows us how to imagine possible futures and assess them for settler or decolonising qualities, in the interests of focusing education right back on learning.

An edited collection follows: Decolonizing Interpretive Research: A Subaltern Methodology for Social Change, edited by Antonia Darder (2019). This builds on the work of Patel and others. Darder introduces the key concepts: how a decolonising methodology and ethics can work, and the importance of centring subaltern voices and naming the politics of coloniality. Then five chapters by current or former doctoral students from subaltern groups serve to exemplify these concepts in practice, and a useful afterword by João Paraskeva pulls together the themes of the book.

Another edited collection is Research as Resistance: Revisiting Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches (2nd edn) edited by Susan Strega and Leslie Brown (2015). This was also outside my budget (Canadian books are so expensive!) and was bought for me by Christine Soltero whose daughter reads my blog. I’m hugely grateful to her because it’s a very useful book. The only annoying thing about it is it doesn’t have an index – I wish academic publishers wouldn’t do that… Anyway, the chapter authors are Indigenous, feminist, and community-based researchers, and the editors promote the idea of a move from resistance to resurgence ‘of knowledges founded in a diversity of spiritualities, philosophies, languages and experiences’ (p 12).

A third edited collection is Research Justice: Methodologies for Social Change edited by Andrew Jolivétte from the US (2015). The cover design includes these words, in a circle: ‘Research justice is achieved when communities of color, Indigenous peoples, and marginalized groups are recognized as experts, and reclaim, own and wield all forms of knowledge and information.’ The first chapter is by the editor, and focuses on radical love as a strategy for social transformation. The second is by Antonia Darder, and all the contributors reflect usefully on how research methodologies can contribute to social change. I wrote a full review of this book for the LSE Review of Books in 2015.

And a fourth edited collection is Towards a New Ethnohistory: Community-Engaged Scholarship Among the People of the River, edited by Keith Thor Carlson, John Sutton Lutz, David M. Schaepe and Naxaxalhts’i (Albert “Sonny” McHalsie) (2018). Ethnohistorians work across the disciplinary boundary between anthropology and history, two disciplines that have tarnished records in the colonial past and present. This book covers a new, decolonising approach that has been used for over 20 years in the lower reaches of the Fraser River which runs through the city of Vancouver to meet the Pacific Ocean. In this approach, academic staff and students work with Indigenous scholars and Indigenous peoples to forge new ways of undertaking community-based ethnohistorical research.

A sole-authored book is Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit by Jo-ann Archibald aka Q’um Q’um Xiiem. For many Indigenous peoples, stories are a key teaching tool. Stories also have a potentially wide range of roles to play in research. This book outlines those roles and advises on how stories can be used effectively and ethically, using the seven principles of storywork: ‘respect, responsibility, reciprocity, reverence, holism, inter-relatedness, and synergy’ (p ix). For the Stó:lō and Coast Salish peoples of Western Canada, these principles form a theoretical framework for making meaning from stories.

The final book in today’s list is Decolonizing Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles, by Clare Land (2015). This book from Australia is by an Indigenous ally and supporter, about being an Indigenous ally and supporter, for Indigenous allies and supporters. It is based on the author’s doctoral and other research and activism, and offers a moral and political framework for non-Indigenous peoples’ solidarity with Indigenous people.

I am also committed to citing these works whenever they are relevant, to do what I can to amplify Indigenous and subaltern voices. However, I hadn’t realised, until I pulled together this list, how biased it would be towards Canadian literature. Another recommendation from a commenter on my previous reading list was the work of Aileen Moreton-Robinson, an Australian Indigenous academic. I want to read her books too, and lots else besides. I am not and never will be an expert on these topics, I am a student of this literature and these methods and approaches. So if you have other works on decolonising methods to recommend, please add them in the comments for everyone’s benefit.

This blog, and the monthly #CRMethodsChat on Twitter, is funded by my beloved patrons. It takes me at least one working day per month to post here each week and run the Twitterchat. At the time of writing I’m receiving funding from Patrons of $54 per month. If you think a day of my time is worth more than $54 – you can help! Ongoing support would be fantastic but you can also make a one-time donation through the PayPal button on this blog if that works better for you. Support from Patrons and donors also enables me to keep this blog ad-free. If you are not able to support me financially, please consider reviewing any of my books you have read – even a single-line review on Amazon or Goodreads is a huge help – or sharing a link to my work on social media. Thank you!

A friend asked me a while ago if I was going to have a break this summer. I couldn’t really see the point when I would only be where I’ve already been for months. But then I realised I was getting tired and, actually, a break from work, at least, would be a good idea.

A friend asked me a while ago if I was going to have a break this summer. I couldn’t really see the point when I would only be where I’ve already been for months. But then I realised I was getting tired and, actually, a break from work, at least, would be a good idea. Sometimes it’s hard to know when to stop. That could be when you’re still having fun and you don’t want to stop even though it’s after midnight and you’ve got to be in work at 9. In my early 20s I could get away with that. In my mid-50s? No chance. The dark sides of not knowing when to stop are dependency and addiction. Then there are the mental ‘ought’s and ‘should’s. I ought to finish reading this book, that I’m not enjoying at all, because the author took so much trouble in its writing. I should keep working on this collaborative piece even though my collaborator hasn’t answered my emails in months.

Sometimes it’s hard to know when to stop. That could be when you’re still having fun and you don’t want to stop even though it’s after midnight and you’ve got to be in work at 9. In my early 20s I could get away with that. In my mid-50s? No chance. The dark sides of not knowing when to stop are dependency and addiction. Then there are the mental ‘ought’s and ‘should’s. I ought to finish reading this book, that I’m not enjoying at all, because the author took so much trouble in its writing. I should keep working on this collaborative piece even though my collaborator hasn’t answered my emails in months. I read novels for pleasure, and I often re-read novels for pleasure too. I’ve read all Terry Pratchett’s books, and if I’m a bit down or feeling overwhelmed, a re-read of one of those will always cheer me up. I sometimes revert to the comfort of children’s books when I’m poorly: Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series is a great favourite. Then there are books I re-read because they’re simply too good to read only once, such as Keri Hulme’s The Bone People which I re-read every few years.

I read novels for pleasure, and I often re-read novels for pleasure too. I’ve read all Terry Pratchett’s books, and if I’m a bit down or feeling overwhelmed, a re-read of one of those will always cheer me up. I sometimes revert to the comfort of children’s books when I’m poorly: Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series is a great favourite. Then there are books I re-read because they’re simply too good to read only once, such as Keri Hulme’s The Bone People which I re-read every few years. I have been working with Indigenous literature on research methods and ethics for over a year now: reading, annotating, thinking, re-reading, and writing from this literature alongside Euro-Western literature on the same topics. During this process I have been reflecting on how I should, and how I do, work with Indigenous literature.

I have been working with Indigenous literature on research methods and ethics for over a year now: reading, annotating, thinking, re-reading, and writing from this literature alongside Euro-Western literature on the same topics. During this process I have been reflecting on how I should, and how I do, work with Indigenous literature. Last week I wrote about

Last week I wrote about  One of the big barriers to doing academic work when you’re not a salaried academic is lack of access to academic literature. Books are one problem, though you can often get hold of them through inter-library loans, national libraries, or (if they’re not too new) cheap second-hand copies online. But academic journals are the major difficulty.

One of the big barriers to doing academic work when you’re not a salaried academic is lack of access to academic literature. Books are one problem, though you can often get hold of them through inter-library loans, national libraries, or (if they’re not too new) cheap second-hand copies online. But academic journals are the major difficulty.

I loved my writing retreat over the last two weeks, but it’s left me feeling a bit unbalanced. No, not like that! Let me explain. All writing and no reading has left me feeling as if I need to follow up my writing retreat with a reading retreat. I love reading as much as I love writing. I’ve been reading intensively about creative research methods for the last couple of years, and now there’s lots of other research-related reading I want to do. But why can it be so hard to find the time?

I loved my writing retreat over the last two weeks, but it’s left me feeling a bit unbalanced. No, not like that! Let me explain. All writing and no reading has left me feeling as if I need to follow up my writing retreat with a reading retreat. I love reading as much as I love writing. I’ve been reading intensively about creative research methods for the last couple of years, and now there’s lots of other research-related reading I want to do. But why can it be so hard to find the time? We all have to read. Including me. Here’s my current TBR pile – and it’s going to grow bigger, as I’ve just finished an online shopping spree to help me catch up on some topics of interest. I’ve made a commitment to reading at least one chapter a day, six days a week. And I’m not the only person who has been thinking along these lines; yesterday @tseenster of the Research Whisperer

We all have to read. Including me. Here’s my current TBR pile – and it’s going to grow bigger, as I’ve just finished an online shopping spree to help me catch up on some topics of interest. I’ve made a commitment to reading at least one chapter a day, six days a week. And I’m not the only person who has been thinking along these lines; yesterday @tseenster of the Research Whisperer  Doing research ethically is not about finding a set of rules to follow or ticking boxes on a form. It’s about learning to think and act in an ethical way. How ethical an action is, or is not, usually depends on its context. Therefore, everything must be thought through as far as possible, because even standard ‘ethical’ actions may not always be right. For example, many researchers regard anonymity as a basic right for participants. However, if your participants have lived under a repressive regime where their voices were silenced, they may feel very upset at the thought of being anonymised, and want any information they provide to be attributed to them using their real names. In such a context, claiming that they must be anonymised because of research ethics would in fact be unethical, because it would cause unnecessary stress to your participants.

Doing research ethically is not about finding a set of rules to follow or ticking boxes on a form. It’s about learning to think and act in an ethical way. How ethical an action is, or is not, usually depends on its context. Therefore, everything must be thought through as far as possible, because even standard ‘ethical’ actions may not always be right. For example, many researchers regard anonymity as a basic right for participants. However, if your participants have lived under a repressive regime where their voices were silenced, they may feel very upset at the thought of being anonymised, and want any information they provide to be attributed to them using their real names. In such a context, claiming that they must be anonymised because of research ethics would in fact be unethical, because it would cause unnecessary stress to your participants.