What can you do to stand out in such a crowd?

Last week I wrote about how to market your academic book. Journal articles, too, benefit from marketing. If you’ve ever had one published, you have probably had one or more emails from the publisher encouraging you to help market your article. It is in the publisher’s interest for you to help them with marketing, because higher visibility usually leads to more citations, and more citations (within two years of publication) help the journal concerned increase its impact factor. It may, though, be in your interest too.

Around two and a half million academic journal articles are published each year on this planet. Generally speaking, if you want your one journal article to be noticed and read among these millions, you need to help it along.

Marketing your journal article begins before you finish writing. A clear and descriptive title, and the most relevant keywords or phrases, will help your article to be visible online. Use as many keywords or phrases as the journal permits. If you find it difficult to come up with enough keywords or phrases, think about what your readers might search for. Also, make sure at least three or four of your keywords or phrases appear at least once in your abstract. This all helps to make your article easier for search engines to find.

The abstract, too, is important. It should tell a clear story in itself, and should include the key ‘take-away’ point you have made. To figure out what that is, it may help to think what headline a journalist would give to a piece based on your article. A well written and structured abstract will entice more people to read further.

Once your article is published, there is plenty more work to be done if you want your research to have an impact. Some publishers make your article free to access online for a specific period or give you a limited number of free eprints. Either way, you can advertise this through email, discussion lists, and social media. Talking of email, it can be useful to add a link to your article as part of your email signature. Also, you can add the link to any online presence, such as your institutional web page and your LinkedIn profile.

If you teach a course for which your article would be suitable material, add it to the reading list. Also, unless it’s open access, check whether your university library subscribes to the journal concerned; if not, recommend it to them.

It’s helpful to write a blog post about your research with a link to your article. This could be on your own blog (if you have one), or on a blog in your field with a wide readership, or on your publisher’s blog. Again, you can advertise the link through social media.

An infographic can be useful too, either as part of a blog post or as a stand-alone information source – or both. Information here on how to create an infographic.

You can make a short video abstract of your journal article and upload it to a video sharing site such as YouTube or Vimeo. This is becoming an increasingly popular way to share information, and there are some great examples online such as this one on social jetlag. It’s not difficult to do, and can be done using a smartphone; there is a tutorial here.

Another option is to create a press release to alert the mainstream media. This is generally only worth doing if the journal article contains information that will interest a lot of people. It also needs to be ‘newsworthy’, e.g. relevant to current news coverage, providing a new perspective on past news coverage, or coinciding with an anniversary. A press release is a short document, usually only a page or at most two, with a specific format; details here.

If this all sounds like a lot of extra work: it is. I’m not suggesting you should do everything listed above; nor am I suggesting that this post is exhaustive. But if you want to make your journal article visible to potential readers, you will almost certainly need to take one or more of these steps.

Last week I wrote about

Last week I wrote about  I recently wrote on this topic citing

I recently wrote on this topic citing  Researchers, research commissioners, and research funders all struggle with identifying good quality arts-based research. ‘I know it when I see it’ just doesn’t pass muster. Fortunately,

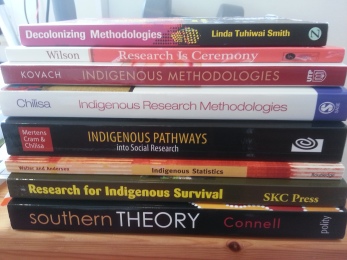

Researchers, research commissioners, and research funders all struggle with identifying good quality arts-based research. ‘I know it when I see it’ just doesn’t pass muster. Fortunately,  I have been working with Indigenous literature on research methods and ethics for over a year now: reading, annotating, thinking, re-reading, and writing from this literature alongside Euro-Western literature on the same topics. During this process I have been reflecting on how I should, and how I do, work with Indigenous literature.

I have been working with Indigenous literature on research methods and ethics for over a year now: reading, annotating, thinking, re-reading, and writing from this literature alongside Euro-Western literature on the same topics. During this process I have been reflecting on how I should, and how I do, work with Indigenous literature. Feedback can feel like a very mixed blessing at times. Positive feedback is a delight to receive, while even the most constructive criticism can come as a crushing blow. Writers are particularly susceptible to this, especially novice writers who haven’t yet learned to separate critique of their writing from critique of themselves. I often meet doctoral students who are very reluctant to show their work to their supervisors, fearing criticism because they’re worried that it’s not very good. If it’s a first draft, of course it’s not very good, and a second draft will also contain problems that have to be fixed. Supervisors need to see this work so they can give feedback, which should include information about:

Feedback can feel like a very mixed blessing at times. Positive feedback is a delight to receive, while even the most constructive criticism can come as a crushing blow. Writers are particularly susceptible to this, especially novice writers who haven’t yet learned to separate critique of their writing from critique of themselves. I often meet doctoral students who are very reluctant to show their work to their supervisors, fearing criticism because they’re worried that it’s not very good. If it’s a first draft, of course it’s not very good, and a second draft will also contain problems that have to be fixed. Supervisors need to see this work so they can give feedback, which should include information about: Last Thursday, Friday and Saturday I was privileged to facilitate the inaugural Creative Research Methods summer school run by

Last Thursday, Friday and Saturday I was privileged to facilitate the inaugural Creative Research Methods summer school run by  Last week I wrote about

Last week I wrote about  In a

In a